Cuzco

An Encounter with the Inca Sun God

The Peruvian city of Cuzco, high up in the Andes mountains, was the capital of the Inca empire from the 13th century until 1533 when it fell to the Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro.

Declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983, the city now attracts over two million visitors a year, many on their way to the iconic ruins of Machu Picchu. Indeed, the American explorer Higham Bingham used Cuzco as a base for his 1911 expedition to discover the ‘Lost City of the Incas.’

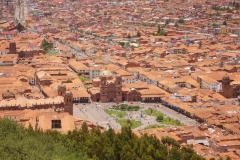

As my plane flew low over the mountains, I could see the city of half a million with its terracotta roofs and church towers covering the valley below. There is not much space for a plane between the rocky peaks and, after having flown past Cuzco, we banked sharply to follow a smaller dale, flying disconcertingly low over the grassy slopes until we entered the main valley and came into land.

Click on the photos below to see the commentary.

I had heard and read many positive things about Cuzco, but I was still surprised by just how pretty the city is and how its Inca history is visible at every turn.

Known as Qosqo in Quecha, the Inca language, the city’s layout was carefully planned and it had an architectural coherence which even the invaders admired. When the Spanish conquered Cuzco in the mid-16th century, they retained its basic structure, but erected Baroque churches and palaces over the ruins of the Inca buildings.

Where the Temple of the Sun – Qorikancha in Quecha – once stood, they built the convent and church of Santo Domingo. The hundreds of gold plates that covered the temple have long since gone, plundered and melted down, but the impressive walls remain.

Elsewhere, the Cathedral – begun in 1559 – and the Iglesia del Triunfo stand on the foundations of Viracocha Inca’s Palace, and the Iglesia de la compañia de Jesús (1576) on those of the palace of Inca ruler Huayna Capac.

Although the Spanish demolished the upper floors of the Inca buildings, they kept many of the lower sections. Today, as you walk round the city, these walls, built of large granite stones, are clearly visible as part of many major buildings. The stones’ irregular shapes, which fit together perfectly without mortar, are thought to be resistant to earthquakes. When one struck in 1950, although colonial-era structures were affected, the sturdy walls built by the Incas stood firm.

Strolling the ancient streets of Cuzco, it was hard to imagine the fierce hand-to-hand fighting that had taken place between the Spanish invaders and the indigenous people all those centuries ago. When Pizarro and his men arrived, they discovered what was technologically a Bronze Age culture, roughly equivalent to that in Ancient Egypt.

The Inca’s weapons – clubs, axes, lances and slings – made of stone and the soft metals bronze and copper were no match for the Spaniards’ arms. They were ineffective against the conquistadors’ steel armour and chain mail, and their own cotton, bronze and copper armour offered no protection against gunshot and swords of tough Toledo steel. And the invaders had horses too, an animal hitherto unknown to the indigenous population.

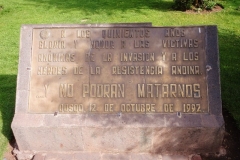

On top of this, the Inca empire was weakened by disease – probably small pox brought by Europeans – and civil war. In this clash of civilisations, although the Incas vastly outnumbered the Spanish, the outcome was probably inevitable. Cuzco’s main square, the Plaza de Armas, is where Pizarro proclaimed his victory over the Inca empire.

Today, the mixture of the Spanish and indigenous cultures can be seen throughout the city – in the people, the clothes, the architecture, and in the art. The 17th century Cuzco school of painting combined European styles with indigenous influences. In the cathedral, a large painting of the last supper shows Jesus and the disciples seated around a table laid with Andean food, the centre piece of which is a roast guinea pig – a local delicacy!

Peru is a gastronomic delight and Cuzco is no exception.

In addition to countless restaurants, the city has a fascinating food market every bit as colourful as the famous Andean textiles and the city’s ubiquitous rainbow flag.

And if you are not tempted by guinea pig cutlets, then sampling a Pisco sour – the traditional cocktail made from the local liqueur, lime juice, egg whites and Angostura bitters – on a roof top bar looking out over the city is a great way to relax after a day visiting the city’s many museums and historic sites.

An even better view of Cuzco can be enjoyed from the hilltop ruins of Saqsaywamán, the fortress of ‘The Satisfied Falcon’ originally built by the pre-Inca culture known as Killke. Some of its colossal, zigzag walls of huge granite stones – the biggest weighing 360 tonnes – are still there, but the three cone-shaped towers that once stood guard are no more.

Protected on three sides by steep slopes, the grey fortress with its three-tiered walls remained an Inca stronghold after the conquistadors had seized Cuzco, but finally fell in 1537 after a long and bloody battle in which thousands of Inca warriors died. Afterwards, many of the walls were dismantled and the stones used for buildings in the city below.

Archaeologists and ethnologists believe that Saqsaywamán was also used for religious purposes. Nowadays, locals use the site to celebrate Inti Raymi, the Inca festival of the winter solstice. Inti was the Inca sun god. There were no celebrations going on when I visited, but you can imagine what a strange sensation it was when, seeing everyone around me suddenly gasping and pointing skywards, I looked up to see a huge sun halo glowing overhead. For a moment, it seemed as if Inti himself was showing us his celestial powers.

If you enjoyed this post and would like to be kept updated of similar postings, why not follow me on Facebook.

RETURN