Berbera

Ancient Sea Port on the Gulf of Aden

In ancient times the port of Berbera in Somaliland was known as Malao. Ships would sail into its harbour on the Gulf of Aden bringing tunics and cloaks, cups, copper and iron and left carrying frankincense, myrrh and cinnamon.

A colourful reminder of the importance of the sea to Berbera and its people

Berbera is also thought to be the town of Bobali, referred to by the 9th-century Chinese scholar Duan Chengshi and which he described as trading in slaves, ivory and ambergris – a waxy substance excreted by sperm whales and used to make perfumes.

Still later, the town was mentioned by the 13th-century Islamic geographer Ibn Sa’id, as well as the scholar and traveller Ibn Battuta some hundred years on.

Some of Berbera’s rich architectural heritage is still standing

Yet, apart from these references – and the sacking of the town by the Portuguese in 1583 – little is known of Berbera until records made in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Its best known feature was its annual fair, reputed to be one of the most important on the East African coast. Traders would arrive with their wares on caravans of camels from cities such as Harar, in what is today Ethiopia, to trade with merchants who had sailed from India.

One of the town’s many colourful doors

In 1888, the British signed a number of treaties with local sultans along the Red Sea coast, which allowed them to set up a protectorate known as British Somaliland, effectively ending centuries of Ottoman rule. Berbera was the capital until 1941 when the British moved their offices to Hargeisa, several hours drive inland.

Minaret, palm trees and blue skies

In 1960 British Somaliland gained its independence before uniting with the former Italian Somaliland five days later to become Somalia.

Following Somalia’s civil war at the end of the 1980s, in 1991 the territory that had previously been the British protectorate declared independence as Somaliland.

The country has never been recognised by the international community and rarely appears on maps as a distinct territory.

There was something reminiscent of Hitchcock about these birds lining up on the wall

Today, the Port of Berbera is valuable as a deep water port, which serves as the region’s main commercial harbour, but the old town still bears the scars of the civil war.

Sea view from the old town

Many parts are dilapidated, with buildings crumbling into ruins. Away from the main roads, its dusty streets are quiet.

Sadly, many of Berbera’s ageing buildings are crumbling away

In some, thick trunks of dead trees lie across across them like giant corpses.

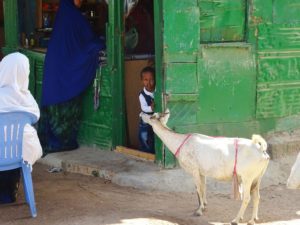

The quiet life

And yet, even if it has lost its former glory, Berbera still feels exotic. With its glimpses of Ottoman architecture, brightly coloured doors guarding unknown secrets, and fishmongers’ walls decorated with hand-painted pictures of fish, even in its current state, Berbera is a traveller’s treat.

One of the town’s more colourful fishmongers

A few women and children venture out into the heat of the sun, while men sit around café tables in the relative cool of the shadows cast by mud-brick walls or those trees that are still standing.

In the midday heat the pace of life is rather sedate

The locals are curious, shy but friendly – the bolder flashing welcoming smiles.

Curiosity

Keen to add some interest to the litres of water I had to drink, in a corner shop I bought a bottle of a dark red cordial. The glass bottle and distinctive label look familiar. Indeed, despite the different name, the locally produced beverage turned out to be Vimto – a once popular drink in the UK and seemingly a cultural leftover from when Berbera was a British colony. I am reminded of the high stacks of tins of Tate & Lyle golden syrup in the souk in Sana’a, Yemen, which was once also ruled from London.

Goats on the town’s Independence Day Monument. The rest of the ‘gang’ scampered before I took the picture.

Goats wander, nibbling at whatever they can find. A gang of them – the word ‘herd’ seems inappropriate – leap on to the base of a rough monument to the 18th of May, independence day, and jostle for space on the narrow ledges that run round it.

As I approach to take a photograph, most of them run off with an air of indignation. In the languid atmosphere of the early afternoon, they are the only thing that moves so quickly.

RETURN